Hear me out. It’s easy to write off Keanu as a silly comedy about a kitten especially in comparison to Get Out, when the latter is one of the most impactful and intelligent movies about race and the black experience that ever existed. But with Keanu, Jordan Peele—along with long-time collaborator Keegan Michael-Key— paved the way for his fanbase to be ready to take him seriously as a director and as someone who has a valuable voice in the dialogue about racial makeup, and the identity woes that come with it. He also gave us hints early on about his predilection for the horror genre. In turn, this allowed Get Out to have massive success and critical acclaim. This exploration of black identity and of the horror genre is apparent all throughout Keanu and also prior to that, on Key & Peele.

Black Identity

As two biracial writers and performers, Key and Peele often explore their own blackness through their art and the unique perspective of being biracial in the Obama-era.

This sums it up pretty well:

The identity struggle surrounding the extent of their blackness plays a crucial role in some sketches from their hit Comedy Central show. Namely, Soul Food, Dating a Biracial Guy, Obama Meet & Greet, and many more.

But while Key & Peele did not shy away from racial conversations, Keanu dove deep into a very specific exploration of black identity. Specifically, that acting “hood” was acting “black”, thus equating a certain attitude with an accepted and expected societal role disparagingly attributed to adult African-American males. Scared that their whiteness was a liability amongst other black people, Keanu looked into the recesses of the role of a black man in society, a theme used in Get Out as well. Rell and Clarence must don a sort of “black character” in Keanu, in order to infiltrate the tough gangster operation who stole Rell’s cat. For them to be respected and welcomed into that organization, they speak in a lower tone of voice, hide their emotions and use the n-word. This functions as a beautifully succinct depiction of the routine code-switching that black men face, and the behavioral expectations that come with skin color.

“Clarence: Yes, I’ll take a white wine spritzer

Rell: Clarence, you can’t talk like that here!”

So while the premise of Keanu is pretty comical (a dramatic search party for a kitten) that doesn’t mean the essence of the comedy and what’s being said underneath isn’t an honest examination of the issues black men face today. Get Out tackles those same themes more directly and more artfully, which is the reason it won Best Original Screenplay at the Academy Awards, but comedy can open up a dialogue and communicate a message just as well.

Comedy is a great way to say what you want to say. To couch truths under jokes and slowly invite your audience to think critically about a situation. Jordan Peele, a massive horror fan, saw the similarities between both comedy and horror genres and used it to his advantage.

The Horror Genre

A lot of horror is predicated upon the same structure as comedy. Build tension → release tension; set up scenario → unexpected reveal. It would make sense that a comedic master could transpose his similar set of skills to horror.

Since Jordan Peele first started concocting Get Out in 2008 when watching the Obama-Clinton debates, both fighting for the Democratic nomination for that year’s election, we know that the story of Get Out was brewing in his head while he made Key & Peele (2012) and Keanu (2016). We also know Peele is a big fan of horror films.

As a showrunner and writer, Peele was able to include many sketches with a horror lean to them in Key & Peele. This is most apparent in parodies of iconic films from the genre, like these…

In the clip above, we see the language of horror being expertly used. Though it’s for comedic purposes and for twisting those situations on their head, the sketches ring true because there’s a deep knowledge of the genre. Dismantling the oft-sought tropes we so commonly associate with horror requires a certain depth of knowledge regarding its mechanics. The comedy, and the point of each sketch, arises in these questions: “what if?” and following that, “how would that look like?”. That is how the idea is formed and what makes up the clear premise of the scene. “What if someone mistook a zombie raccoon with a zombie during the apocalypse? How would that look like?”

“What if the torturer gets tortured? How would that look like?”

“What if zombies were racist? How would that look like?”

The frenetic dialogue, the quick pacing of the camera moment, the visual vocabulary of special effects, color tones and wardrobe/makeup. They’re all present here. We can see Peele’s knowledge of horror at play.

By using the comic device of “what ifs?”, Peele allowed us to explore the horror genre through the lens of critical thinking. Most horror genre movies have a message. Dawn of the Dead is about mindless consumerism, The Babadook is about grief, and so on…

In the same vein, Get Out is about slavery and the prison industrial complex or more globally as the experience of being a black man in contemporary American society.

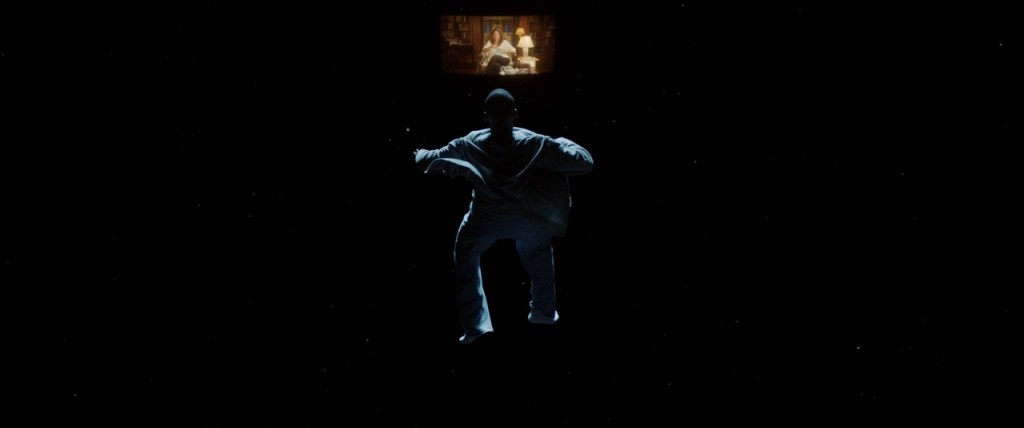

Get Out uses that technique of “what if” by showing us a manifestation of what it feels like to be black today. “What if hypocritical blank support and the appropriation of black culture was concretized in an apparent way?” “How would that look like?”. We see the deeply meaningful and gripping sequence in Get Out when the hero, Chris, falls in the empty hypnotic abyss of the “sunken place”. In the same way, Keanu showed this sort of other-wordly, dream-like, metaphorical sequence when Clarence gets visited by Keanu as a spiritual guide. Both scenes are very different in tone and in message, but by including that sort of surrealistic scene in Keanu, Peele primed his audience to be ready for an even more impactful use of that type of scene in Get Out.

Though both Key & Peele and Keanu helped pave the way for Get Out, Keanu ultimately cemented Peele as a feature film screenwriter who can create box office appeal. Sketches are short by nature, and writing Keanu proved that Peele could sustain the pace of a longer movie. I’m very thankful for both these movies for different reasons and I believe that Peele’s previous work informed Get Out and that his departure from comedy to horror is less unexpected than we might think.